There are many forms of Urdu poetry e.g. ghazal, qasida, marsiya, masnavi, etc. Of these, the most popular form is the ghazal.

In the 1940s a revolt started in Urdu poetry in India against the ghazal form of Urdu poetry by so called ‘progressive’ and ‘revolutionary’ writers, because of which many Urdu poets stopped writing ghazals.

They thought it inappropriate to continue writing progressive poetry in this traditional and classical form. Some even thought it shameful.

In 1945 in a large gathering of Urdu writers in India, speaker after speaker criticised ghazal, and a near unanimous resolution was passed stating that modern Urdu poetry should be in free verse or some other form without the traditional shackles of the ghazal, so that progressive and modern ideas could be conveyed in liberated form.

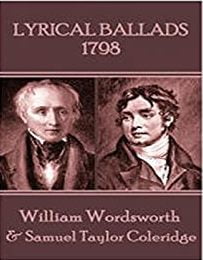

This was somewhat like the Romantic Revival in the late 18th century in English poetry (launched by Wordsworth and Coleridge in their ‘Lyrical Ballads’) which rebelled against the rigid classicism of Alexander Pope and others. But unlike the Romantic Revival, this ‘revolt’ was short lived.

This was somewhat like the Romantic Revival in the late 18th century in English poetry (launched by Wordsworth and Coleridge in their ‘Lyrical Ballads’) which rebelled against the rigid classicism of Alexander Pope and others. But unlike the Romantic Revival, this ‘revolt’ was short lived.

Before going further into this, we must understand what is ghazal.

A ghazal is short poem consisting of a set of rhyming couplets called shers (usually 5 to 15 in each poem) which are independent yet usually indirectly linked with a common theme.

A sher must have 5 characteristics, otherwise it is not a sher. These are (1) radeef (2) qaafiya (3) matla (4) maqta and (5) beher

To explain this, let us take a poem of Majrooh Sultanpuri :

dushman kī dostī hai ab ahl-e-vatan ke saath

hai ab ḳhizāñ chaman meñ naye pairahan ke saath

sar par havā-e-zulm chale sau jatan ke saath

apnī kulāh kaj hai usī baankepan ke saath

kis ne kahā ki tootgayā ḳhanjar-e-firang

seenepe zaḳhm-e-nau bhī hai dāġh-e-kuhan ke saath

jhoñke jo lag rahe haiñ nasīm-e-bahār ke

jumbish meñ hai qafas bhī asīr-e-chaman ke saath

‘majrūh’ qāfile kī mere dāstāñ ye hai

rahbar ne mil ke lootliyā rāhzan ke saath

(1) Radeef means the last word or words in a line (misra) in a sher, and they have to be exactly the same. In the first sher of the ghazal (called matla) the radeef must be present in both the misras, but in the following shers this is necessary only in the second misra.

In the above ghazal, the radeef is ‘ke saath‘. The first two shers have the same radeef even in the first misra, but that is not so in the succeeding shers. For example, in the third sher there is no radeef ‘ke saath’ at the end of the first misra, but only in the second misra.

(2) Qafiyah means the word or words preceding the radeef. These word or words need not be exactly the same, but they must rhyme.

In the above ghazal, the qafiyas are rhyming words ending with ‘an’ e.g. ahle-vatan, pairahan, jatan, baankepan, kuhan, chaman, etc

(3) Matla, as explained above, means the first sher in a ghazal. It must have radeef in both its misras. In the following shers radeef is compulsory only in the second misra.

(4) Maqta is the last sher of a ghazal. It usually has the ‘takhallus’ or pen name of the poet, e.g. Ghalib, Faiz, Firaq, etc

(5) Beher means the metre, which may be short, medium or long, but the same metre must be strictly maintained throughout the ghazal.

Thus it is evident that though there is freedom to choose any topic for writing a ghazal, there is no freedom in expressing it. There is freedom in content, but not in form.

The progressive Urdu writers revolted against this non freedom in form of the ghazal.

Perhaps they were influenced by English poets of the Romantic Revival, T.S.Eliot, Walt Whitman, etc who revolted against rigid forms in poetry and experimented in blank verse etc.

The progressive Urdu writers in India perhaps thought that liberal and democratic ideas in the modern age needed freer forms of expression.

What they perhaps overlooked is that English and American literature have different traditions and backgrounds than Indian literature.

The ghazal, originating from Arabia, had been developed by Hafiz, Rumi, etc in Persia, and further developed by Mir, Ghalib, etc into powerful forms of poetic expression.

Progressive and revolutionary ideas, too, require to be expressed in a powerful form to serve the masses. For example, take the poem of Bismil, the Indian revolutionary who was hanged by the British rulers :

“ Sarfaroshi ki tamanna ab hamaare dil mein hai

Dekhna hai zor kitna baazu-e-qaatil mein hai

Waqt aane de tujhe bataa denge ai aasmaan

Abhi se hum kya bataaen kya hamaare dil mein hai “

This ghazal has so much power that it became the battle anthem of the Indian freedom struggle. By observing the strict rules of the ghazal gave it more power, not less.

Or take the well known ghazal of Faiz ‘Hum parvarish-e-lauh-o-qalam karte rahenge’, or the ghazal whose first sher is :

“ Gulon mein rang bhare baad-e-naubahaar chale

Chale bhi ao ki gulshan ka kaarobaar chale “

Can anyone say that these poems became less effective because they observed the strict rules of radeef, qafiyah, beher, etc ? No, they became more powerful.

I submit that free verse can be used for expressing ideas, but then it will lose its power.

Perhaps the dislike of ghazal by the progressive writers was because many Urdu poets were using ghazal to write on topics unconnected with the people’s problems and aspirations, and only expressing their individual agony, love for a woman, etc. What they forgot was that that was not the fault of ghazal as a mode of expression per se, but its use.

Today, the people of the Indian subcontinent need powerful poetry to inspire them in their struggle for a better life.

If poetic forms other than ghazal can be devised for this, there would be no objection, but it is submitted that ghazal can also play an important role, and should not be abandoned, as the ‘progressives’ demanded. ![]()

Also Read:

Can the Draconian Money Grab Bill (FRDI) Revisit Again in its new Avatar (FSDR)?

The Worrisome Chinese Space Programme

Caste Based Census Should Become a Reality

Pandemic Profits and Politics – the saga of India’s “La Casa De Papel”

Watch video:

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayTV.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayTV.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT

Copyright © Punjab Today TV : All right Reserve 2016 - 2025 |