With just 1.53 per cent of India’s geographical area, Punjab has been and is contributing a significant share to country’s food security ever since the advent of Green Revolution in mid-1960s.

Punjab accounted for 74 per cent contribution of wheat and 16.3 per cent of rice to the central pool in 1970-71. It was 73 per cent and 45.3 per cent in 1980-81, respectively. The respective share declined to 35.46 per cent and 25.53 per cent in 2018-19.

In absolute sense, however, Punjab’s contribution of wheat and rice to the central pool increased to 12.69 million tonnes and 11.33 million tonnes in 2018-19.

Clearly, very high proportion of wheat production and exorbitantly high proportion of rice production of Punjab is still going to the central pool.

One can understand that some of the erstwhile food-deficit states have now become either food self-sufficient or have been able to generate some surplus. As a consequence, the importance of Punjab, Haryana and Western UP in the central pool has declined. But it needs to be kept in mind that the above mentioned states are going to stay as important food security providing states.

The irrigation intensity in Punjab increased from 54 per cent in 1960-61 to 99.9 per cent in 2017-18. The all India average irrigation intensity is still hovering around 45 percent. This means nearly 55 percent of the area under crops is not having assured irrigation and agriculture there is either dry or rain-fed.

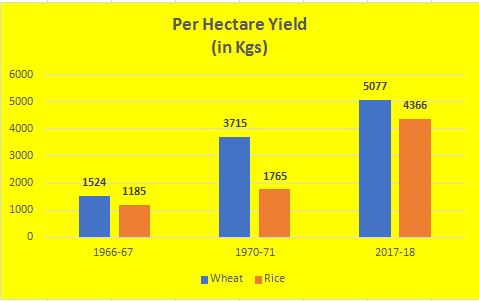

The per hectare yield of wheat increased from 1524 kg in 1966-67 ( the beginning of green revolution) to 4696 kg in 1999-2000. The per-hectare yield of wheat was 5077 kg in 2017-18, which was 3.33 times higher than 1966-67.

As compared to it, the all India average per hectare yield of wheat increased from 887 kg in 1966-67 to 3368 kg in 2017-18. The all India average yield of wheat was 58.20 per cent in 1966-67 and 66.34 per cent in 2017-18 of the yield in Punjab.

The total production of wheat in Punjab increased from 2.45 million tonnes in 1966-67 to 17.83 million tonne in 2017-18, an increase of 7.28 times.

The per hectare yield of rice in Punjab increased from 1185 kg in 1966-67 to 4366 kg in 2017-18; an increase of 3.66 fold over 1966-67. As compared to it, per hectare average yield of rice in India increased from 863 kg in 1966-67 to 2576 kg in 2017-18 which is 59 per cent that of Punjab.

The total production of rice in Punjab increased from 0.34 million tonne in 1966- 67 to 13.38 million tonne in 2017-18; an increase by 39.35 times.

As a consequence, India became self-sufficient in food-grains but Punjab had to pay a heavy price in terms of serious depletion of water table and deterioration of soil health, besides doing away with diversified-organic-cropping pattern. The water-intensive paddy crop, which was never a natural crop and staple diet of Punjab, became the villain of peace as it led to an ever increasing extraction of ground water with an exponentially increasing number of tube-wells.

As a matter of fact, Punjab has been virtually exporting its ground water to the food-grain deficient states of India in the form of rice.

Over the period of time there developed an ‘agri-water nexus’, better read ‘paddy-water nexus’ as wheat is much less water intensive crop.

Now when some of the other states have become either self-sufficient or surplus in food-grain production, the central government is advising Punjab to diversify its cropping pattern without any enabling policy regime.

Paradoxically, among the major rice producing states of India, Punjab is the most inefficient in water productivity of rice as it is using 5337 litres of water to produce one kg of rice while the all India average is 3875 litres of water. West Bengal uses 2605 litres of water to produce one kg of rice.

As compared to West Bengal, Punjab uses more than two times more water to produce one kg of rice.

Water consumption in total rice production in Punjab increased from 16642.5 billion litres in 1980-81 to 59046.8 billion litres in 2013-14.

Out of it 13449.2 billion litres went to the central pool in 1980-81 and 43261.7 billion litres in 2013-14.

Punjab contributed 11.833 million (0.011833 billion) tonnes of rice to the central pool in 2017-18 and to produce this quantity the state used 63152.72 billion litres of water; out of that more than 70 per cent was ground water.

Significantly, 88.46 per cent of the total rice production (13.38 million tonnes) of Punjab went to the central pool in 2017-18. In other words 88.46 per cent of the water used in rice production in Punjab went to the central pool.

This is virtual water export from Punjab and is the classic example of ‘rice-water export nexus’.

The area under paddy increased from 2.27 lakh in 1960-61 to 30.64 lakh hectares in 2017-18. During a span of 58 years, the area under paddy increased by 13.50 times.

The area under paddy increased from 2.27 lakh in 1960-61 to 30.64 lakh hectares in 2017-18. During a span of 58 years, the area under paddy increased by 13.50 times.

The area under wheat increased from 14 lakh hectares in 1960-61 to 35.12 lakh hectares in 2017-18. Over the period of 58 years the area under wheat increased by 2.51 times.

Wheat accounted for 99.78 per cent of the total area under Rabi cereals and paddy accounted for 96.30 per cent of the area under Kharif cereals in 2017-18. The respective share in 1960-61 was 95.50 per cent and 33.24 per cent.

Thus, wheat has been the main crop among the Rabi cereals while paddy was having a much lower importance in the Kharif cereals. Wheat and paddy together accounted for 98.13 per cent of the total area under cereals and 97.68 per cent of the total area under food-grains in 2017-18.

The respective share in 1960-61 was 75.71 per cent and 75.32 per cent. These two crops accounted for 83.89 per cent of the total cropped area in Punjab in 2017-18 as compared to 34.38 per cent in 1960-61.

The above data clearly highlights that paddy was not the main crop in the Kharif cereal; it was only after the advent of green revolution that paddy became the most important crop, rather the only crop in Kharif season. In fact, green revolution drastically changed the cropping pattern in Punjab; from diversified to only wheat-paddy agriculture.

To meet the increasing demand for irrigation, especially for rapidly increasing area under paddy (highly water intensive crop), the dependence on ground water increased in a big way which, in turn, led to a mind-boggling increase in the number of tube-wells.

The number of tube-wells in the agricultural sector increased from 1.92 lakh (1.01 lakh diesel operated and 0.91 electric operated) in 1970-71 to 14.76 lakh in 2018-19 (1.40 lakh diesel operated and 13.36 electric operated), an increase of 7.69 times or 668.75 per cent.

Compared to it, the net area sown (NAS) increased from 40.53 lakh hectares in 1970-71 to 41.18 lakh hectares in 2018-19 (an increase of only 1.02 times or 1.60 per cent).

The gross cropped area (GCA) on the other hand increased from 56.78 lakh hectares in 1970-71 to 78.39 lakh hectares in 2018-19 (an increase of 21.61 lakh hectares; 38.06 per cent).

Evidently, the number of tube wells registered highly disproportionate rise as compared to the rise in net area sown and gross cropped area. It is mainly because of the multi-fold increase in area under paddy, very high cropping intensity (190 per cent, up from 126 in 1960-61) and 100 per cent irrigation intensity (up from 54 per cent in 1960-61).

The increase in NSA from 37.50 lakh hectares (75 per cent of geographical area) in 1960-61 to 42.66 lakh hectares (85 per cent of geographical area; highest by far in absolute and percentage terms) in 1997-98 and the increase in gross cropped area from 47.23 lakh in 1960-61 to 79.41 lakh hectares in 2001-01 (by far the highest) have also been very significant factors in increasing dependency on ground water and tube-well irrigation.

The irrigation intensity in Punjab increased from 54 per cent in 1960-61 to 99.9 per cent in 2017-18. The total irrigated area in Punjab increased from 2020 thousand hectares in 1960-61 to 4124 thousand hectares in 2017-18 (an increase of 1236 thousand hectares; 42.80 per cent).

The area under tube-well irrigation increased from 829 thousand hectares (41.04 per cent of total irrigated area and 22.06 per cent of NAS) in 1960-61 to 2948 thousand hectares (71.48 per cent of the total irrigated area and 71.47 per cent of NAS) in 2017-18.

As a result of exorbitantly high number of tube-wells and very high cropping and irrigation intensity the water table went down at a fast rate. The number of over-exploited blocks increased from 53 (44.92 per cent) in 1984 to 105 (76.09 per cent) in 2013 and further to 109 (78.99 per cent) in 2017.

The net annual ground water availability for irrigation development was 2.44 million acre feet (MAF) in 1984 which decreased to 0.22 MAF in 1999. It dwindled to minus 8.01 MAF in 2004 and further to -12.02 in 2011.

Such a dark situation reached due to over exploitation of ground water. The aggregate gross ground water draft in Punjab was 149 per cent in 2013 which increased to 166 per cent in 2017.

As per the latest report (2019) of the Central Ground Water Board, in 18 of all the 22 districts of Punjab the draft was more than 100 per cent in 2017. Among them 7 districts are such in which the draft is in the range of 208 and 260 per cent.

In another 4 districts the draft is between 151 and 200 per cent and in 7 districts the draft varies between 101 and 150 per cent. Out of the remaining 4 districts, in two the draft is 98 and 99 per cent and in another two it is 74 per cent and 76 per cent, respectively.

Thus, in 18 districts there is serious over-drafting of ground water while in another two districts the situation is critical and still in another two it is semi-critical.

Thus almost the entire Punjab is in for serious water scarcity as there is no safe zone as far as water extraction is concerned.

The computations done by this author shows that during 1996-2016, out of 17 districts, 12 have witnessed a significant decline in water table ranging from 3.55 metres to 22.05 meters.

The computations done by this author shows that during 1996-2016, out of 17 districts, 12 have witnessed a significant decline in water table ranging from 3.55 metres to 22.05 meters.

These are predominantly paddy growing districts. Paradoxically, the annual average rainfall decreased from 673 millimetres (mm) during 1975-85 to 438 mm during 2009-13. In 2014 it was 385 mm and in 2016 it was 427 mm and 598 mm in 2018. Thus, the average rainfall in Punjab has witnessed a significant decline but there has been wide variation spatially and temporally.

It is quite worrisome that out of the total geographical area of Punjab (50, 36,200 Hactare-Ha), the area where ground water table is more than 10 metre deep has been continuously increasing.

It was 7, 49,600 Ha (14.9%) in June 1989, 10, 23,400 Ha (20%) in June 1992, 14,15,100 Ha (28%) in June 1997, and 22,07,300 Ha (44%) in June 2002.

It further increased to 30,41,800 Ha (61%) in June 2008, 32,36,100 Ha (64%) in June 2010, 33,10,400 Ha (65%) in June 2012 and 33,177,00 Ha (65%) in June 2016.

There is 343 per cent increase in the area having ground water table of 10 metre or more during a span of 27 years.

This necessitates crop diversification which has been a subject of debate for the last about 35 years but nothing tangible came out on the ground. The Johl Committee-1 (1986) and II (2002), constituted by the government of Punjab for restructuring and diversifying agriculture,made a significant recommendation for shifting substantial area (20 per cent) from under paddy but it did not cut any ice.

Rather, area under paddy increased over the period of time, from 11.83 lakh hectares in 1980-81 to 30.64 lakh hectares in 2017-18.

The Draft Agricultural Policy (2013) and 2019 prepared by the Punjab State Farmers’ Commission also recommended crop diversification by shifting substantial area from under paddy but so far the state neither has agricultural policy nor water policy.

Paradoxically, even the Punjab Water Development and Regulatory Authority, constituted in 2020, has not included irrigation under its purview.

Paradoxically, even the Punjab Water Development and Regulatory Authority, constituted in 2020, has not included irrigation under its purview.

Significantly, as per the norms of irrigation set by the Punjab Agricultural University paddy needs 25 irrigations in a short span of about four months besides a lot of water used at the time of transplanting by way of puddling and it requires standing water for three to four weeks in the beginning.

The farmers mainly use flooding method of irrigation, a highly water consuming method. Micro irrigation techniques (sprinkler and drip irrigation) and use of water saving technologies are yet to hold foot in Punjab.

As compared to paddy, wheat needs 4-6 irrigations. Bajra, maize, barley, pulses and oilseeds need 3 to 4 irrigations. Sugarcane requires 20-22 irrigations but its duration is one year. Potato and cotton requires 4-6 irrigations. Excess number of irrigations, especially to paddy, is another serious problem, may be because of free power.

High amount of evapotranspiration (ET value) in sugarcane (1.35 metre), paddy (0.65 metre), cotton (0.60 metre), maize (0.48 metre), pulses (0.45 metre) and wheat (0.38 metre), etc., is leading to enhanced pressure on ground water and depletion of water table.

Though sugarcane’s ET value is little more than two times that of paddy yet its total amount of evapotranspiration is much lower than that of paddy as the area under sugar cane was only 0.97 lakh hectares (3.17 per cent of area under paddy and 2.76 per cent of area under wheat) and that of cotton 2.91 lakh hectares (9.50 per cent of area under paddy and 8.29 per cent of area under wheat) in 2017-18.

Quality of water is also a serious challenge in Punjab as there are a number of quality hazards tagged with ground water such as Arsenic, Fluoride and Salinity in many regions of the state.

Increasing water pollution due to urbanization, industrialisation and increased use of fertilisers and pesticides is causing water quality deterioration of surface and ground water resources (CGWB, 2018).

The contamination of groundwater at shallow depth is mainly being caused by surface water pollution. The physico-chemical of shallow ground water in the state indicates wide variations in mineral contents.

On the basis of Electrical Conductivity (EC) of water it is classified as ‘Fit, Marginal and Un-fit’ while Residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) is the indicator of salinity and alkalinity in the water. According to CGWB (2018) nearly 50-60 per cent of Punjab’s groundwater up to the depth of 60 meters is fresh and fit.

It is generally found in north, north-eastern and central parts of the state comprising of Amritsar, Gurdaspur, Hoshiarpur, Jalandhar, Kapurthala, Nawanshahar, Ropar, Ludhiana, Fatehgarh Sahib and SAS districts.

Approximately, 20-30 per cent of the groundwater generally found in north-western and central parts of the state comprising districts of Tarn Taran, Patiala, Sangrur, Barnala and Moga is moderately saline and of marginal quality.

Nearly 15-25 per cent of the groundwater is saline/alkaline and not fit for irrigation use and generally found in isolated patches south and south-western parts of the state in Muktsar, Bathinda, Mansa and Sangrur.

Groundwater in South and south-western districts of the state namely Faridkot, Ferozepur, Mukatsar, Bathinda, Mansa, Barnala and Sangrur contain varying concentration of soluble salts and its use for irrigation has an adverse effect on agricultural yield and production.

The problem is more severe in terms of salinity in the districts of Mukatsar, Mansa and Bathinda.

Poor groundwater quality is another serious challenge in Punjab as 14.72 per cent (848628 hectares) of state’s area was having poor groundwater quality as on 13 March 2017 ((CGWB. 2018).

Some studies by various agencies have also highlighted the significant contents of Nitrate, Fluoride, heavy metals and radio-active element such as uranium, beyond permissible limits, in south and south-western part of the state.

It is worth mentioning that high fluoride content in groundwater may be due to the heavy use of phosphatic fertilisers in agriculture in Punjab. The deteriorating quality of surface and groundwater is leading to increasing water pollution and resultantly higher incidence of water borne diseases in the state.

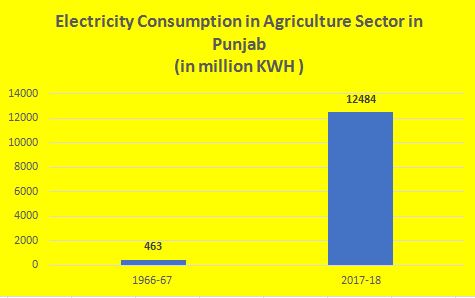

The electricity consumption in agriculture increased from 463 million KWH in 1970-71 to 12,484 million KWH in 2017-18; an increase of nearly 27 times. As compared to it, the gross cropped area increased only by 1.38 times while the irrigation intensity increased by just by 29 percentage points.

The depletion of water table and frequent deepening of tube-wells led to increase in submersible electric motors from 710 thousands in 2010 to 979 thousands in 2017. This led to an ever increasing number of high BHP electric motors for ground water extraction.

Due to increasing demand for energy the amount of power subsidy to agriculture sector (because of free power) increased from Rs. 900 crore in 2002-03 to Rs. 5197 crore in 2016-17 and shall be 6728 crore in 2021-22.

The moot questions are that:

Though these questions need a larger debate, yet, the policy support and open-ended assured public procurement at minimum support price ever since mid-1960s and the free power to agriculture from 1997 may be the most prominent reasons for such a scenario.

The phasing out paddy or shifting substantial area from under paddy would require a policy mix and incentives to farmers, both by the central and state governments.

The farmers would have to be assured for at least the same amount of net income from alternative crops which they are getting from wheat-paddy crop rotation.

The farmers would have to be assured for at least the same amount of net income from alternative crops which they are getting from wheat-paddy crop rotation.

This requires an enabling environment for developing and growing such crops which could become at least economically viable alternative to paddy.

This study has tried to find out such alternative crops but due to numerous constrains they are not providing any sustainable alternative to paddy.

The Punjab Agricultural University has been trying to promote some alternative crops and farmers have tried their hands on some of those crops but could not become popular with the farmers as marketing of those crops at a viable price and income deficit compared to wheat-paddy rotation are some of the serious bottlenecks.

Paradoxically, green revolution dismantled the pre-green revolution diversified cropping pattern and now we are trying to have the diversified agriculture!

Despite some of the efforts for developing alternative crops, there is hardly anything on ground. The economic viability of alternative crops is a major hurdle in the way of crop diversification.

There is absence of enabling environment for the promotion of alternative crops such as maize, cotton, basmati rice (fine quality rice), pulses and oil seeds, vegetables and fruits.

Interestingly, maize accounted for 15 per cent of the total area under cereals while pulses accounted for 29.48 per cent of the total area under food-grains in 1960-61.

In 2017-18, the share of maize in total area under cereals dwindled to 1.63 per cent and that of pulses to 0.45 per cent in the total area under food-grains.

Under the prevailing circumstances, it may not be possible to attain the pre-green revolution status for maize and pulses but there is a considerable scope for increasing the area under these crops. That would require R&D and supporting policy instruments if we really want to address the problem of fast depleting water table, soil health and environment.

The effective implementation of MSP for all the remaining 21 crops besides paddy and wheat would certainly provide an incentive to farmers for growing crops other than wheat and paddy.

As a matter of fact, the Government of India has been advising Punjab, Haryana and Western UP ever since 2010 to shift significant area form under paddy to less water consuming alternative crops without any supporting policy intervention.

In early 2018, the Vice-Chairman of the NITI Aayog, Dr. Rajiv Kumar, cautioned the government of Punjab that the country no longer needs Punjab’s rice the way it was needed earlier and strongly ‘advised’ Punjab to go in for crop diversification alas without any enabling and supporting policy intervention.

When there was no public response from the Punjab government then I wrote an article, Punjab’s virtual water export, in which I argued that the government of India and the NITI Aayog must understand that Paddy was not promoted by farmers of the above mentioned states instead the farmers were made to promote paddy on a big scale by the policies of central and state governments.

And now they are giving sermons (Matlab nikkal gaya toh pehchante nahin) to the farmers to go in for crop-diversification.

Nearly 14 years prior to that, on 24 August 2004, The Tribune carried my article, Punjab economy depends on water: State resources lost in building food security, but neither the state government nor the central government pay any heed to it. Even the Johl Committee Reports (1986 and 2002) have been buried under the dust.

Now, if the governments and policy makers are serious then their concern must be supported by compatible policies and their effective implementation.

Now, if the governments and policy makers are serious then their concern must be supported by compatible policies and their effective implementation.

The farmers alone would not be able to do any effective crop-diversification but they would certainly go in for diversification if they are sure to get at least the same net income per hectare which they are getting from the wheat-paddy crop combination.

It can be possible by a policy-combination of R&D in high yielding varieties of seeds of alternative crops and assured procurement at the minimum support price of those crops. The touchstone, however, shall remain the per hectare net income from alternative crops.

The arm-twisting strategy for crop-diversification by way of recently enacted three agri-laws by the central government is neither a right nor an ethical approach. Such an approach is against the natural justice as the promotion of paddy was done by the enabling environment created by the policies of the Union Government.

At the same time, ensuring an efficient and optimum use of natural resources, especially water, is sine qua non.

If we are not able to save water then days are not far off when agriculture would not be economically viable and the sustainability of business as usual model of agriculture will be under great pressure.

If we are not able to save water then days are not far off when agriculture would not be economically viable and the sustainability of business as usual model of agriculture will be under great pressure.

At many places in Punjab the water table has gone so deep that we have started using the third layer of the aquifer.

Already there are echoes that if we did not pay any serious heed to the fast depleting water table the state is going to face a desertification.

In view of the alarming situation, we must read what is written on the wall, the sooner the better, and respond to the situation on war footing so that Punjab remains a liveable place. ![]()

Also Read:

Death Registers Expose The Gujarat Model Of Counting The Dead

The saga of an Unborn Vikas – Driving India Backwards?

Pandemic Profits and Politics – the saga of India’s “Money Heist”

Opposition Unity For GE 2024: Myth Or Reality?

युद्ध के मैदान में खेले जा रहे खेल से कौन हो रहा मालामाल?

Watch video:

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayTV.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayTV.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT

Copyright © Punjab Today TV : All right Reserve 2016 - 2025 |