Assessing the Progress, Challenges, and Future Prospects of the Indian Republic

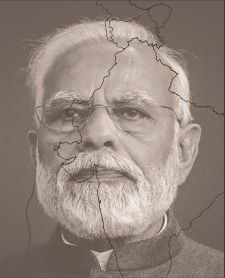

AS WE HAVE just completed 75 years as a republic, it is time to look back and introspect on our progress—or lack thereof—in various spheres and to conduct a reality check on whether we have lived up to the expectations of our freedom fighters and the framers of the Constitution.

Indeed, in some sectors, we have done well, if not exceptionally. In others, we have not reached a satisfactory level, and in some areas, we appear to be regressing.

When the British first arrived in India, the country was indeed the “sone ki chhiriya” (golden bird), with a 25% share of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 1820, this share had declined to 16%, further dropping to 12% by 1870, and plummeting to just 4% at the time of independence. Today, it stands at 3.8%—far from the glorious past, with only a slight upward trajectory.

The Modi government has claimed that India is now a five-trillion-dollar economy and is set to become the third-largest economy in the world by the end of this decade.

However, we still have a long way to go to ensure prosperity for vast sections of our population. Unfortunately, the latest figures show that the gap between the super-rich and the very poor is widening. Even the middle class is bearing the brunt of inflation and declining employment opportunities.

Competitive politics has led to a culture of freebies, with each party trying to outdo the other by announcing unproductive expenditures, such as cash doles to women and free rations to nearly half the population. It is evident that the burden of such expenditure falls on the middle class—particularly on the 5% of the population that pays income tax.

In addition to income tax, a multitude of revenue sources have been created through various other taxes. While taxation is necessary for national development, the misuse of these funds on unproductive expenditures is a cause of frustration for honest taxpayers.

In terms of other progress indicators over the past 75 years, we have come a long way—but not as far as we were capable of. For instance, at the time of independence, India’s average life expectancy was just 32 years. Today, it stands at approximately 72 years, though healthy life expectancy remains around 62 years.

In terms of other progress indicators over the past 75 years, we have come a long way—but not as far as we were capable of. For instance, at the time of independence, India’s average life expectancy was just 32 years. Today, it stands at approximately 72 years, though healthy life expectancy remains around 62 years.

Healthcare services have improved considerably in urban areas but continue to lag in rural regions. While those who can afford private care have access to state-of-the-art hospitals, government-run hospitals—particularly in rural areas—remain in a dismal state.

For a country historically known for its ancient centres of learning, India had a literacy rate of just 12% at the time of independence. The official literacy rate has now risen to 72.9%, but for women, it remains lower at 64.64% on average.

In the field of agriculture, India has made significant progress. From a country plagued by acute food shortages and starvation, we have emerged as a food-surplus nation. There was a time when we depended on foreign aid and had to rely on poor-quality grain shipments from America.

In the field of agriculture, India has made significant progress. From a country plagued by acute food shortages and starvation, we have emerged as a food-surplus nation. There was a time when we depended on foreign aid and had to rely on poor-quality grain shipments from America.

Thanks to the Green Revolution, we are now in a much stronger position. However, the economic status of farmers has not improved proportionally. In fact, farmers’ average income has failed to keep pace with inflation, leading to widespread economic distress in the agricultural sector.

From a nation that depended on foreign imports even for basic items like needles in 1947, India has come a long way in manufacturing and exports. The push for self-sufficiency, or Atmanirbhar Bharat, has led to the production of not only essential goods but also advanced satellites, aircraft, and weaponry.

Similarly, we have made great strides in infrastructure development from the poor state left behind by the British. The railway network, which was about 55,000 kilometers at independence, has now expanded to over 1,26,000 kilometers. The highway network has grown from around 21,000 kilometers to 1,36,000 kilometers.

As the world’s largest democracy, India has maintained a fairly strong democratic record. However, a major blot on this history was the imposition of the internal Emergency in 1975, during which even fundamental rights were suspended. While India recovered from that period, successive governments have continued to undermine individual liberties. The last decade has been particularly troubling in this regard.

Draconian laws such as the UAPA have been blatantly misused against political and ideological rivals, including journalists. Additionally, enforcement agencies like the CBI, Enforcement Directorate, and Income Tax Department have been weaponized by the government, tarnishing India’s democratic credentials.

Another area where we have performed poorly is the justice delivery system. As per the latest figures, over five crore cases are pending in high courts and subordinate judiciary, with an equal number awaiting resolution in executive courts. Hearings drag on for years—sometimes even decades.

Despite concerns raised by prime ministers and chief justices of India, no concrete steps have been taken to reduce the backlog. Yet, the judiciary remains the last hope for the common man seeking justice.

One of the most alarming setbacks has been the increasing communalization of society. Efforts to deepen the Hindu-Muslim divide are dragging the nation backward.

The blatant attempt to sow seeds of distrust between communities has led to a sharp rise in the number of individuals who were once considered fringe elements.

Moreover, a significant portion of those who were once moderates have now turned radical, fueled by the false narrative that India’s 14.5% Muslim population could surpass the Hindu majority.

India must strive for inclusivity, ensuring that all sections of society—regardless of caste, creed, or gender—progress together.

We must avoid the pitfalls that have consumed societies dominated by radical ideologies elsewhere in the world. Our focus should remain on upliftment, development, and progress, ensuring that all citizens enjoy the true benefits of freedom.

Given India’s immense potential and the advantage of having the youngest population in the world, with a median age of 27 years, there is no reason why we cannot be global leaders in the years to come. ![]()

_________

Also Read:

India Must Not Miss This Bus

Our VIP Culture: A Growing Class of Parasites

Will Leaders Rise to the Demographic Challenge?

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT