Cinema, Communal Narratives, and the Weaponization of History

AS COMMUNAL HATE spreads through the use of history in political battlegrounds, new dimensions have been added to this trend in recent years. Apart from propaganda and indoctrination through RSS shakhas, social media, the BJP’s IT cell, and mainstream media—particularly many TV channels—films have also contributed to prevailing misconceptions in society.

In the recent past, movies like The Kerala Story and The Kashmir Files have gripped society with a mania of hate. Other, less successful films, such as Swatantraveer Savarkar, 72 Hoorain, and Samrat Prithviraj, have also attempted to shape public perception.

Now, Chhava—a film running to packed houses in Maharashtra and across the country—is further escalating this hate. This is not a historical film; rather, it is based on the novel Chhava by Shivaji Samant. The filmmakers have already had to apologize for inaccuracies in the movie.

The film selectively picks a few incidents from Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj’s life to project Aurangzeb as cruel and anti-Hindu.

In its 126-minute runtime, nearly 40 minutes are devoted to the torture of Sambhaji Maharaj—a section where the filmmaker may have taken significant creative liberties. The entire narrative frames medieval history as a battle between noble Hindu kings and evil Muslim rulers.

Sambhaji Painting Late 17th Century

Sambhaji Maharaj was the eldest son of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. As Shivaji established his kingdom, he appointed several Muslim officers. Maulana Haider Ali was his confidential secretary, and among his 12 generals were Muslims such as Siddi Sambal, Ibrahim Gardi, and Daulat Khan.

When Shivaji confronted Afzal Khan, he was advised to carry iron claws—given to him by his subordinate, Rustom-e-Jaman. After Shivaji killed Afzal Khan, the latter’s secretary, Krishnaji Bhaskar Kulkarni, attempted to attack him.

On Aurangzeb’s side, Raja Jai Singh led the Mughal army against Shivaji. Shivaji was summoned to Aurangzeb’s court and later imprisoned. However, he managed to escape with the help of a Muslim prince, Madari Mehtar.

The ideological forebears of Hindutva, Savarkar and Golwalkar, raised questions about Sambhaji’s character, accusing him of indulgence in wine and women. As a result, Shivaji imprisoned him in Panhala Fort. Later, Sambhaji allied with Aurangzeb in battles against both Shivaji and Adilshah of Bijapur.

If we condemn Aurangzeb’s actions, what should we say about present-day bulldozers razing the homes of accused individuals—who happen to be Muslims—without any legal trial?

In the succession battle after Shivaji’s death, Sambhaji’s half-brother, Rajaram (son of Shivaji’s wife Soyrabai), attempted to poison him. When the conspiracy was uncovered, Sambhaji had many Hindu officers executed. Aurangzeb sent his general, Rathod, to fight Sambhaji. After Sambhaji was captured, he was humiliated and subjected to torture—a segment that the film exaggerates significantly.

This film has further reinforced negative perceptions of Aurangzeb, portraying him as excessively cruel in dealing with his opponents. However, rather than engaging in whataboutism, it is important to understand the nature of medieval kingdoms. Many rulers inflicted cruelty on their enemies with impunity.

Historian Ruchika Sharma notes that when the Chola kings defeated the Chalukya army, they beheaded General Samudraraj and mutilated his daughter. Emperor Ashoka’s Kalinga war is infamous for its brutalities. Medieval rulers routinely employed extreme violence against their enemies, and their actions cannot be judged by modern standards.

Aurangzeb

If we condemn Aurangzeb’s actions, what should we say about present-day bulldozers razing the homes of accused individuals—who happen to be Muslims—without any legal trial?

Similarly, historical accounts describe Hindu kings using brutal tactics. One Hindu ruler had a fort atop a hill where conspirators were thrown into a deep valley with their hands and feet tied.

In his book, Bal Samant describes the atrocities committed by Shivaji’s army during the plunder of Surat. Armies and atrocities were closely associated; while cruelty is condemnable, it was not unusual. When Sambhaji’s Marathas attacked Goa, a Portuguese account (cited by historian Jadunath Sarkar) states: “Nowhere else in India has such barbarity been seen.”

While such narratives must be scrutinized carefully, they indicate that violence was widespread, though its degree varied.

Was Aurangzeb Anti-Hindu?

Aurangzeb was neither Akbar nor Dara Shukoh. He was orthodox and did not favor Hindus or non-Sunni sects of Islam. However, he was also a master of political alliances and had numerous Hindu officers in his administration. As Prof. Athar Ali points out, Hindus comprised the highest proportion of officials in Aurangzeb’s administration—33%.

While Aurangzeb did destroy some temples, he also donated to many others, including Kamakhya Devi (Guwahati), Mahakaleshwar (Ujjain), Chitrakoot Balaji, and the Krishna temple in Vrindavan.

Shivaji Painting In British Museum

Similarly, Shivaji donated to the Sufi dargah of Hazrat Baba Bahut Thorwale. Victorious kings often destroyed places of worship associated with rival rulers. Historian Richard Eaton (Frontline, Dec-Jan 1996) notes that communal historians selectively highlight temple destruction by Muslim rulers while ignoring their donations to Hindu temples.

Aurangzeb imposed the jizya tax 22 years into his rule. It was exempted for Brahmins, women, and disabled individuals. Contrary to popular claims, it was not a means of forced conversion but a property tax (1.25%), whereas Muslims paid zakat (2.5%).

As for the torture of Sikh Gurus, it was undoubtedly wrong, but the underlying cause was a political power struggle between the Sikh leadership and the Mughal administration.

The Danger of Selective Historiography

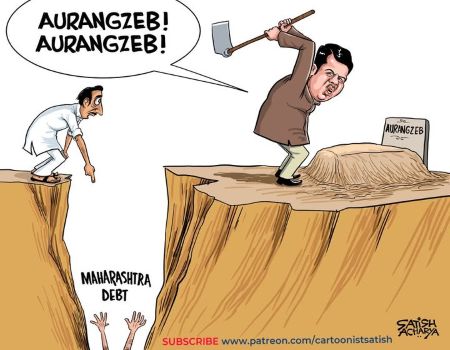

Communal historians are working overtime to cherry-pick historical events that fit their narrative while ignoring the broader context of medieval politics.

Aurangzeb Kabar

Kings used religion to mobilize armies—Hindu rulers invoked Dharma Yuddh, while Muslim rulers used Jihad.

Right-wing historians selectively present sources that align with their communal framework, viewing kings through a religious lens rather than acknowledging that their primary goal was the expansion of power and wealth.

This selective historiography fuels divisive politics, posing a significant threat to the Indian Constitution. ![]()

Also Read:

‘WhatsApp’ History: A Clash of Academia and Political Narratives

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT