As he nears retirement, CJI D.Y. Chandrachud’s legacy is shadowed by silence on pivotal issues and missed chances to curb executive overreach.

THESE DAYS, Mr. D.Y. Chandrachud, Chief Justice of India, is reflecting on, and perhaps concerned about, the legacy he will leave behind when he retires next month. And well he might. He was elevated to this position at perhaps the most critical juncture in the nation’s recent history, when every democratic and humanistic principle was being crushed under an unstoppable electoral machine and a government on steroids.

His last four predecessors had let the country down and walked away into an inglorious sunset, content with their sinecures and post-retirement benefits. Never before had the nation nurtured such high expectations or vested so much hope in an heir apparent to the Chief Justice’s chair. The legacy of Mr. Chandrachud will be that he, too, let the nation down.

His last four predecessors had let the country down and walked away into an inglorious sunset, content with their sinecures and post-retirement benefits. Never before had the nation nurtured such high expectations or vested so much hope in an heir apparent to the Chief Justice’s chair. The legacy of Mr. Chandrachud will be that he, too, let the nation down.

“Honesty,” said Shakespeare, “is the best legacy”; sadly, his Lordship has been less than honest, with us and to himself. At seminars, keynotes, valedictory functions, and convocations—even in his obiter dicta—he has always hit the right notes, stressing individual liberty, freedom of speech, religious pluralism, constitutional safeguards, and the court’s responsibility to hold the executive accountable.

But within the sanitized confines of his courtroom, he seemed to lack the courage of his convictions, leading many to wonder whether he had any convictions at all. In the words of Alexander Pope, he was “willing to wound but afraid to strike.” That is not a proper foundation for a judge’s legacy.

The Supreme Court’s records will speak for themselves in times to come. Justice Chandrachud had many opportunities to do the right thing, to restore the autonomy of institutions, such as through the appointment of Election Commissioners, and to rein in rampaging state governments, notably with the bulldozers of U.P., Nuh, and Uttarakhand. He could have taken a stand to prevent illegal surveillance of citizens, as seen in the Pegasus “inquiry,” where the Union government dared to tell him it would not cooperate. Similarly, he had a chance to restore statehood in Jammu and Kashmir and to uphold legitimately elected governments brought down by illegal means, as in Maharashtra.

He also had the opportunity to restore faith in the electoral process through repeated petitions to return to paper ballots or fully verify VVPATS. Additionally, he could have questioned an unaccountable Election Commission on its dubious actions and decisions—such as delays in uploading voter counts, the non-issue of Forms 17C, mismatches in votes cast and counted, and the failure to act under the Model Code of Conduct against high-ranking government officials.

Umar Khalid

Perhaps worst of all, under his Lordship’s watch, thousands of social activists, journalists, dissenters, and academics continue to languish in jail without trial or even bail. Umar Khalid’s bail petitions have been adjourned, I believe, 14 times, with judges successively recusing themselves without explanation.

The Bhima Koregaon accused are being released on bail in instalments, as if justice were a divisible commodity. Some have even died under these conditions (80-year-old Stan Swamy) or due to inhuman treatment while in custody, the most recent being Prof. G.N. Saibaba, a man with 90% disability who was kept in jail for almost a decade without being convicted. Most outrageously, when he was acquitted by the Bombay High Court, the Supreme Court took the unprecedented action of convening on a holiday to stay the High Court order!

And which historian can forget the Ram Janmabhoomi order, where the faith of the majority community, not legal evidence, formed the basis of a judgment that should shame any country or judiciary?

Hon’ble judges celebrating the Babri-Ram Janmabhoomi judgment at a five-star hotel

Or the photo of the Hon’ble judges celebrating the judgment with a dinner and wine at a five-star hotel—a judgment which (as per press reports at the time) none of them signed, yet another first in our sorry history.

Under Justice Chandrachud’s watch, the Center was allowed to further defenestrate the Collegium with tactics of delay, selective approvals, or simply sitting on recommendations: he made some noises initially, then adopted a strategic silence.

The same fate met dozens of habeas corpus petitions, now interred in the court’s registry. The SEBI (Hindenburg) and Pegasus inquiries were never pursued to logical conclusions, and the Electoral Bonds judgment was hastily shut down, an enforced closure on what looked very much like a sovereign extortion racket.

For all his high oratory about the majesty of the court and accountability of the executive, to the best of my knowledge, not a single government functionary has actually been punished—not even the Returning Officer of the Chandigarh mayoral election, caught red-handed in an electoral “flagrante delicto” in an official video. Not the encounter specialists, the bulldozer bureaucrats, or the regulatory agencies, even when the Court found the arrests illegal both procedurally and on merits.

It’s true that Mr. Chandrachud himself was not directly responsible for all these actions and inactions, decided by other benches, but as Chief Justice, he shares the blame. He is, after all, the head of the institution, its chief administrator, the primus inter pares, and most importantly, the Master of the Roster. If you take credit for the thunder, you must take the blame for the drought.

It’s true that Mr. Chandrachud himself was not directly responsible for all these actions and inactions, decided by other benches, but as Chief Justice, he shares the blame. He is, after all, the head of the institution, its chief administrator, the primus inter pares, and most importantly, the Master of the Roster. If you take credit for the thunder, you must take the blame for the drought.

He watched in silence as some High Courts became politicized, their judges openly expressing religious allegiances, exhibiting biases in judgments, joining political parties, and even standing for elections immediately after retiring, or attending religious conclaves. The issue here is not legality but the spirit of constitutional values they are supposed to uphold.

Justice Chandrachud himself often reminded us that the spirit of the law is as important as its letter. Therefore, it was important for him to have spoken out, to remind his brother judges of the inappropriateness of their behavior and the judiciary’s own Restatement of Values of Judicial Life, which the Supreme Court issued in 1997.

PM Narendra Modi Visits CJI DY Chandrachud’s Residence For Ganesh Puja

The Chief Justice of India occupies a moral pedestal far higher than his rank on the Warrant of Precedence—his every word carries weight and can influence the nation’s discourse. Given his fondness for preaching, he should have reiterated the moral and ethical red lines for judicial conduct. By not doing so, he has, by default, become a party to the judiciary’s decline during his tenure.

To be fair, he has passed some praise-worthy judgments, such as decriminalizing homosexuality and upholding transgender rights. But the true test of a superior judge lies in his ability to stand up to the executive, and in this respect, his judgments have been few and far between.

In fact, it requires effort to recall them. Far too much time was spent grandstanding, wasting the court’s time on issues it had no business getting into—the farmers’ protest and the RG Kar Medical College cases are two instances where he seemed to play to the gallery.

Also Read: Chandrachud vs Chandrachud: a Battle to Ethics

Both cases diminished the court’s image—the farmers ignored its suggestions in the first case, and the doctors summarily rejected orders to return to work in the second. Perhaps someone should have reminded the Chief Justice of the first law of public administration: do not seek to expand your area of concern beyond your area of influence.

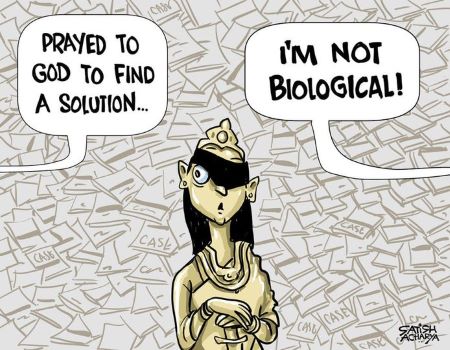

Lady Justice

Even as he leaves, Justice Chandrachud indulges in empty symbolism: recently, he inaugurated his version of the statue of Justice, calling it Lady Justice. This figure now has no blindfold (“justice is not blind”) and holds a copy of the Indian Constitution instead of a sword.

I, for one, am unmoved by these histrionics. For me, the three monkeys of the Mahatma better reflect the state of our justice system today—blind, deaf, and speechless.

One writes this piece not with joy but with a deep sense of regret for what could have been. Here was a man—a judge, a scholar, a decent and compassionate human being, with a penetrating legal mind—who could have done much to pull the country out of the morass it is being pushed into.

Also Read: NO MORE BLINDFOLDED? The New Lady Justice

The tragedy is not that he failed to do so, but that he chose not to. If only he had learned from the words of Mother Teresa, an exemplar of virtuous service whose legacy will endure:

“The world is changed by your example, not your opinions.”

Farewell, your Lordship; we wish you well, despite your betrayal of the nation. ![]()

Courtesy: avayshukla.blogspot.com

Disclaimer : PunjabTodayNews.com and other platforms of the Punjab Today group strive to include views and opinions from across the entire spectrum, but by no means do we agree with everything we publish. Our efforts and editorial choices consistently underscore our authors’ right to the freedom of speech. However, it should be clear to all readers that individual authors are responsible for the information, ideas or opinions in their articles, and very often, these do not reflect the views of PunjabTodayNews.com or other platforms of the group. Punjab Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the views of authors whose work appears here.

Punjab Today believes in serious, engaging, narrative journalism at a time when mainstream media houses seem to have given up on long-form writing and news television has blurred or altogether erased the lines between news and slapstick entertainment. We at Punjab Today believe that readers such as yourself appreciate cerebral journalism, and would like you to hold us against the best international industry standards. Brickbats are welcome even more than bouquets, though an occasional pat on the back is always encouraging. Good journalism can be a lifeline in these uncertain times worldwide. You can support us in myriad ways. To begin with, by spreading word about us and forwarding this reportage. Stay engaged.

— Team PT